The successes and setbacks of BRI in Southeast Asia: A focus on the Philippines

Author(s)/Editor(s): Dr. Gary Ador Dioniso and Jovito Jose P. Katigbak

Publication year: 2025

Publication type: Policy Brief

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This policy brief critically assesses China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Southeast Asia with a spotlight on the Philippines while exploring emerging opportunities for Australia in the region’s infrastructure landscape. While the BRI has seen significant achievements such as doubling trade with partner countries and creating 421,000 new jobs, it faces mounting concerns over economic viability, unfavorable loan terms, displacement of indigenous peoples, and environmental issues. This paper underscores the mixed results across Southeast Asia, with varying experiences in countries like Cambodia, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Indonesia. In the Philippines, the New Centennial Water Source - Kaliwa Dam Project exemplifies these challenges, facing economic viability concerns, indigenous peoples' displacement, and environmental issues. Under President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the Philippines has withdrawn from the BRI in 2023 and diversified its funding sources by forging closer ties with like-minded countries such as Australia. Hence, this policy brief argues that Australia can help fill the post-BRI infrastructure gap by focusing on three infrastructure development-related policies, namely: (i) institutionalising Partnerships for infrastructure Initiative principles and processes; (ii) promoting "open, clean, and green" projects; and (iii) showcasing successful Australian-backed infrastructure projects in the Philippines and globally. Together, these steps offer a pathway to deepen Philippines–Australia cooperation while supporting sustainable and inclusive infrastructure development in the region.

INTRODUCTION

In October 2023, the China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) celebrated its tenth anniversary through the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation which was attended by 23 heads of state or government. This is the smallest contingent since the First Forum in 2017 with 30 attendees and the Second Forum in 2019 with 37 participants. During his speech, Chinese President Xi Jinping unveiled eight major policy actions that the country intends to mainstream in its future BRI-related endeavours. These include: (i) building a multidimensional Belt and Road connectivity network; (ii) supporting an open world economy; (iii) carrying out practical cooperation; (iv) promoting green development; (v) advancing scientific and technological innovation; (vi) supporting people-to-people exchanges; (vii) promoting integrity-based BRI cooperation; and (viii) strengthening institutional building for international Belt and Road cooperation.

In hindsight, it can be stated that BRI is characterised by both impressive accomplishments and perennial challenges. To illustrate, China's trade in goods with BRI countries doubled from USD1.04 trillion in 2013 to USD2.07 trillion in 2022, with an average annual growth rate of 8%. Over the same period, two-way investment between China and BRI countries exceeded USD270 billion. Chinese enterprises have likewise invested USD57.13 billion in economic and trade cooperation zones in Belt and Road countries by the end of 2022, which resulted in 421,000 new jobs for locals. At the start of 2023, China has signed more than 200 BRI cooperation agreements with 151 states and 32 international organisations, and it estimates that about 40 million people globally have been lifted out of poverty through BRI’s contribution.

Despite these achievements, BRI-related projects, specifically in Southeast Asia, are persistently hounded by common issues of economic (un)viability of the project, unfavourable terms of the loan agreement, socio-cultural concerns such as the displacement of indigenous peoples, and environmental issues such as biodiversity loss and freshwater protection. As a response, the BRI has also been scaled up to include the Green Silk Road, Digital Silk Road, and Health Silk Road. China is likewise promoting “high-quality BRI cooperation” founded on three pillars, namely: (i) extensive consultation, joint efforts, and shared benefits; (ii) open, green, and clean approach; and (iii) pursuit of high-standard, people-centred, and sustainable development.

Although the BRI has apparently addressed the abovementioned challenges, it is still worth perusing the experiences of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries in implementing projects under the said initiative, with a specific focus on the Philippines.

BRI IN ASEAN: MIXED BAG

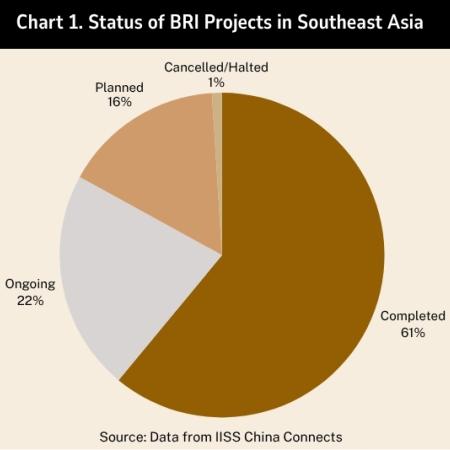

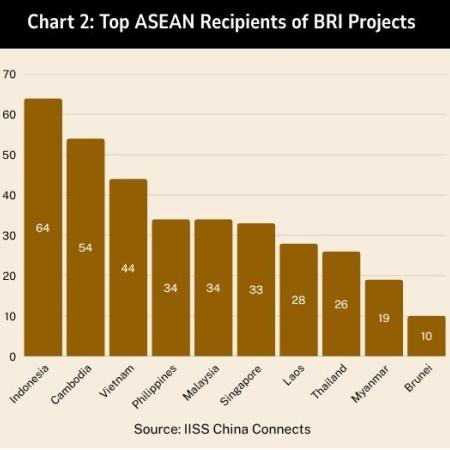

As of July 2025, there are 254 BRI completed projects, 89 ongoing, 66 planned, and six cancelled/halted in Southeast Asia. The primary types of projects are low carbon power generation, telecommunication, 5G, highways/roads, and fossil fuel-based power generation. More specifically, Indonesia (64) has received the largest number of completed and ongoing projects, excluding those cancelled/halted, followed by Cambodia (54), Vietnam (44), and Philippines (34). Malaysia (33), Singapore (33), Laos (28), Thailand (26), Myanmar (19), and Brunei (10) make up the remaining figure. The succeeding paragraphs provide an overview of the varying BRI experiences of several ASEAN countries.

First, Cambodia has availed a total of almost USD3.3 billion in concessional loans and grants from China to fund its infrastructure projects. It is pushing for the creation of a railway project connecting Vientiane, Pakse (Laos) with Siem Reap, Phnom Penh, and Sihanoukville port (Cambodia). Cambodia believes that Chinese investments have been beneficial for them, and that the BRI has promoted greater connectivity in Asia.

Second, no major work on any China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) project moved ahead during the previous government and negotiations paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the takeover of the military in 2021. There are nine CMEC projects in the pipeline and two CMEC projects (i.e., Kyaukphyu Deep-Sea Port, Muse-Mandalay railway) are progressing, although they are yet to be implemented. Challenges focus on debt sustainability, adverse environmental impact, and negative social impact.

Third, the International Land-Sea Trade Corridor (or western corridor) is a key cooperation project under the Chongqing Connectivity Project, while the Qinzhou Port in Guangxi is at the intersection of water and land routes in the Western Corridor. The western corridor connects Chongqing and Western China with Singapore and Southeast Asia as a whole. It faces problems of insufficient sources of foreign trade goods as there is considerable imbalance between southbound cargo transportation and northbound cargo transportation in the western corridor.

First, Cambodia has availed a total of almost USD3.3 billion in concessional loans and grants from China to fund its infrastructure projects. It is pushing for the creation of a railway project connecting Vientiane, Pakse (Laos) with Siem Reap, Phnom Penh, and Sihanoukville port (Cambodia). Cambodia believes that Chinese investments have been beneficial for them, and that the BRI has promoted greater connectivity in Asia.

Second, no major work on any China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) project moved ahead during the previous government and negotiations paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the takeover of the military in 2021. There are nine CMEC projects in the pipeline and two CMEC projects (i.e., Kyaukphyu Deep-Sea Port, Muse-Mandalay railway) are progressing, although they are yet to be implemented. Challenges focus on debt sustainability, adverse environmental impact, and negative social impact.

Third, the International Land-Sea Trade Corridor (or western corridor) is a key cooperation project under the Chongqing Connectivity Project, while the Qinzhou Port in Guangxi is at the intersection of water and land routes in the Western Corridor. The western corridor connects Chongqing and Western China with Singapore and Southeast Asia as a whole. It faces problems of insufficient sources of foreign trade goods as there is considerable imbalance between southbound cargo transportation and northbound cargo transportation in the western corridor.

Next, there are two projects in Vietnam recognised as funded under the BRI, namely, the Phu Lac Wind Power and Hanoi Metro Line 2A (Cat Linh – Ha Dong). Specific problems encountered by the latter project include ineffective project management, technical challenges, contentious land acquisition and resettlement processes, safety issues during construction, weak coordination among implementing agencies, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, funding challenges, and project extension.

Lastly, two landmark projects in Indonesia under the BRI are the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway Project and the Industrial Park for Nickel Smelting. Both undertakings are concrete manifestations of President Jokowi’s new developmentalism approach and the government’s attempt to improve the country’s position in the global supply chain. However, the railway project was supported by a poor feasibility study without a credible socio-environmental impact assessment and sound financial planning. It was also complicated by conflicting bureaucratic interests, ineffective coordination between central and local governments, and the mobilisation of anti-China sentiment during electoral events. For the industrial park project, there were complaints about the entry of illegal Chinese foreign workers and the presence of poor safety standards for workers. It was similarly challenged by the pervasiveness of local politics and the tension between local and Chinese labourers.

Correspondingly, China has responded to several apprehensions and concerns of ASEAN countries regarding BRI. It has released the “Guidelines on Debt Sustainability and Risk Management for BRI Projects” and entered public-private partnerships to address debt-trap diplomacy concerns. In the environmental aspect, China launched the green silk road, built ecological corridors as exemplified by the Boten-Vientiane railway, and restricted the creation of new coal-fueled power plants overseas. It similarly employed numerous locals in specific projects across BRI countries such as Indonesia, Laos, and the Philippines.

NOTES FROM THE PHILIPPINE EXPERIENCE

There is conflicting data regarding the actual number of BRI projects that are being implemented in the country. Nevertheless, the IISS China Connects website identifies 46 BRI-related projects in the Philippines. Many of them (20) advance infrastructure connectivity (e.g., bridges, railways, airport), followed by ICT-related (12) projects (e.g., 5G connectivity, cybersecurity), and the remaining projects focus on health, trade, and power generation.

Notably, the Philippines encountered the same issues and challenges faced by ASEAN countries relative to the implementation of BRI ventures. In particular, the New Centennial Water Source - Kaliwa Dam Project (NCWS-KDP) is intended to supply 600 million liters of water daily and benefit around 17.46 million people (or about 3.49 million households) in Metro Manila, Rizal, and Quezon. It is projected to cost around USD374.5 million, which will be financed by Chinese ODA loan (85%) and the PHL government (15%). NCWS-KDP was scheduled for construction over the period 2019-2023 but several impediments and controversies delayed the timeline. It is currently at 22% completion rate. Recent reports note that construction will conclude in 2026 and operations will begin late 2026/early 2027.

A primary concern relates to the economic viability of the project. Several studies have underscored the unviability of the Kaliwa Dam. A 2021 study noted that the Kaliwa Dam is economically burdensome to the Philippines while skeptics posit that President Rodrigo R. Duterte signed the Chinese-funded project, instead of more sustainable options, to “boost his own political standing, increase the pace of construction, and to be able to more easily reward local elites with the cooperation of the more-pliable Chinese partners.” Nevertheless, a 2019 MWSS study claimed that the expansion potential of the Kaliwa Dam project would far exceed the proposed Kaliwa Intake Weir, and that the accompanying water treatment of the former is cheaper than the latter.

Further, indigenous peoples (IPs) have expressed worries about the displacement of around 10,000 members of Dumagat indigenous tribes and the loss of their livelihoods. The construction of the dam was put on hold in 2022 because of the protest of the IPs. The Metropolitan Water Works and Sewerage System (MWSS) was also accused of not executing the right process to secure Free, Prior Informed Consent (FPIC). MWSS stated that the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples had already issued a Certification Precondition. It has also entered into mutually beneficial agreements with IPs, local government units, and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to meet all explicit conditions under the environmental compliance certificate.

The Kaliwa River watershed is also part of the Sierra Madre Biodiversity Corridor. Several groups have opposed the NCWS-KDP and are calling for its abandonment due to the “long-term, irreversible environmental damage to the Sierra Madre and its biodiversity.” In spite of this, the Environmental DENR-Management Bureau issued an environmental compliance certificate in 2019 which enabled the continuance of the project. In 2022, the DENR-Protected Area Management Board issued the approval of clearances as a prerequisite for a Special-Use Agreement on Protected Areas.

ENTER AUSTRALIA: OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSIDERATIONS

Evidently, the Philippines has had a complex relationship with China’s BRI. The country initially joined the initiative to deepen global trade and develop infrastructure through Chinese investments, but recent local and global developments have prompted it to retreat from the BRI. Under the administration of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the Philippines withdrew from several major BRI projects (i.e., railway lines) in 2023 due to funding delays and tense exchanges with China. Thus, the country has actively diversified its funding sources for major infrastructure projects by forging closer ties with like-minded partners such as Japan, the United States, and other international financial institutions.

Australia, guided by its "Invested: The Philippines to 2040" strategy, took notice of the Philippines’ growth potential and has been actively nudging Australian investors to venture into the latter specifically in key sectors such as resources, infrastructure, green energy transition, education, digital economy, and agriculture food. Recent data reveal that more than 300 Australian companies employ about 40,000 Filipino workers in the Philippines encompassing business process outsourcing, renewable energy, digital health services, infrastructure, banking, and education sectors. Notwithstanding the robust economic partnership between Philippines and Australia, three equally important policy considerations are still worth emphasising.

Institutionalise key principles and processes of the Partnerships for Infrastructure (P4I) Initiative

Infrastructure and related projects are vulnerable to geopolitical risks due to lengthy gestation periods, which are subject to political cycles, developments in bilateral ties, and cross-border spats. Philippines and Australia may hence explore the institutionalisation of P4I-related processes and principles to uphold policy continuity. Specifically, the Australian government may proactively promote the establishment of more public-private partnerships, the development of climate-resilient infrastructure, and the realization of inclusive infrastructure to address local displacement concerns.

Mainstream the implementation of “open, clean, and green” projects

Responsible and concerned agencies must practice good governance ideals such as transparency, participation, and accountability to effectively respond to the interests and concerns of their constituents. Transparent and competitive procurement processes and sound environmental impact assessments must be strictly observed during the initiation and planning stages. Moreover, effective, impartial monitoring of projects during the performance and control stage may be attained by engaging third-party actors such as civil society organisations and non-government organisations.

Spotlight successful Australian-backed infrastructure projects in the Philippines and globally

To further embed Australia in the consciousness of potential Philippine-based business partners, there is a need to intensively highlight world-class, high-quality infrastructure that was developed through the “Australian way”. More importantly, public diplomacy efforts may be undertaken to increase awareness among the Filipino public of the preferential terms and sustainable practices being advanced by the Australian government and entities. Greater visibility in social media may perhaps result in more clamor for Australian involvement in infrastructure projects across the Philippines. Indeed, this would be beneficial for both parties in their respective endeavors, namely: Australia deepening its entanglement in Southeast Asia; and the Philippines diversifying its partnerships amid a tumultuous environment.