Urban governance for managing climate change risks: Rethinking political mandates for metropolitan structures in the Philippines

Author(s)/Editor(s): Dr Weena Gera

Publication year: 2025

Publication type: Policy Brief

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This policy brief highlights the urgent need to strengthen integrated urban governance to manage climate risks and disaster hazards in Philippine metropolitan regions. Rapid urbanisation is increasing the complexity of urban challenges, particularly the need for coordinated action across jurisdictions for large-scale infrastructure projects such as integrated flood management. The Philippine New Urban Agenda identifies clear multi-level governance and metropolitan coordination as national priorities. However, the current decentralisation framework, based on the 1987 Constitution and the 1991 Local Government Code, remains inadequate. While inter-local cooperation is encouraged, there is no political mandate for metropolitan governance, making collaboration largely dependent on shifting political alignments. Case studies from Metro Cebu and Metro Iloilo illustrate these systemic weaknesses. To address these gaps, this brief recommends incremental reforms, starting with strengthening the role of Regional Development Councils as key coordinating bodies for metropolitan sustainability and resilience. Over time, these efforts should lead to the creation of formal metropolitan authorities for highly urbanised regions. Ultimately, it calls for amending the Local Government Code to define and institutionalise political powers for metropolitan governance structures, enabling cities to respond more effectively to the complex territorial and political challenges of urban climate resilience and sustainable development.

INTRODUCTION

Cities in the Philippines are undergoing rapid demographic, environmental, and socio-economic changes, with five in 10 Filipinos now living in urban areas and 84 percent expected to do so by 2050 (UN-HABITAT, 2024). The growth of cities, however, has overwhelmed the capacity of local authorities to develop and maintain adequate social and physical infrastructure especially in managing climate and disaster risks at scale. These are evident with pronounced urban sprawls with excessively high levels of congestion, pollution, and the massive formation of marginal settlements and slums, which are especially vulnerable to hazards.

Cities are also acutely susceptible to emerging global uncertainties such as climate change-induced disasters, particularly massive flooding often brought by tropical storms, and exacerbated by poor land use, river rehabilitation, drainage management, and waste management systems. Considering that the Philippines has consistently been among the most disaster-prone countries in the world - most recently ranked as the highest-risk among 193 countries with a risk index of 46.91 based on the 2024 World Risk Report - the associated risks of rapid urbanisation are profound for the country.

Often these stresses faced by cities transcend city/municipal boundaries and local political jurisdictions (Metropolis 2024). Pollution, congestion, large-scale flooding, and mass migration are symptoms of unmanaged externalities inherent in rapid urbanisation. These challenges expose the limitations of city-based approaches to urban risk governance and call for a rethinking of the politico-territorial and inter-jurisdictional structures of metropolitan regions. With growing interdependence between cities and their surrounding areas, development and risk management now demand inter-local and regional collaboration. This underscores the need for integrated urban governance through vertical and horizontal institutional coordination in planning, implementing, and operating infrastructure and services (HUDCC n.d.). As cities understand this, they design and implement resilience and sustainability strategies that best align with the scale of the challenge, and engage with transboundary partners and stakeholders, redefining established political, functional and geographical borders. Many of these actions, however are fragmented. This compels for an examination of the viability of inter-jurisdictional initiatives for urban climate resilience at the metropolitan level and at scales beyond traditional political city jurisdictions.

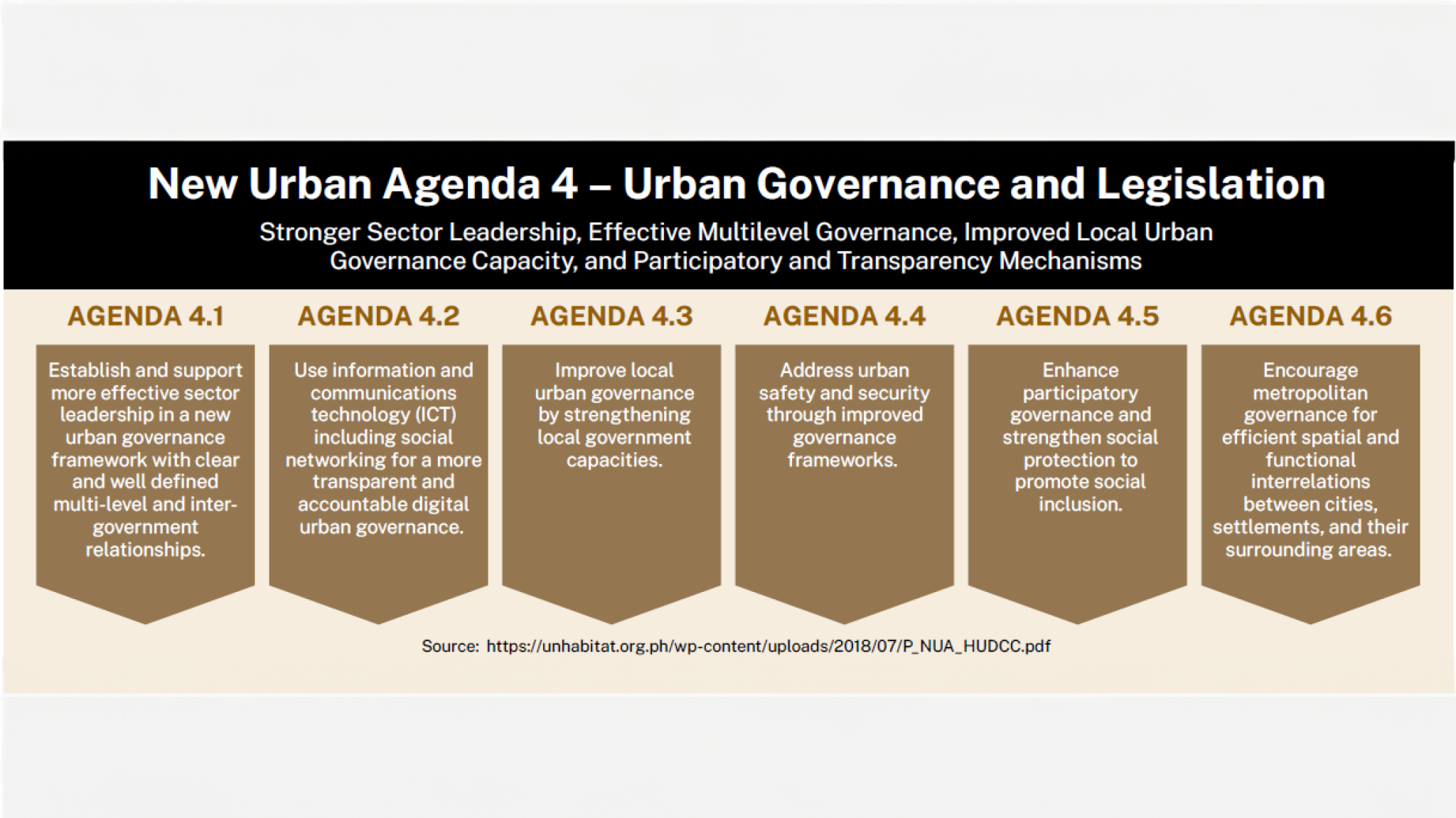

The Philippine government recognises these shifts and the complexity of urban challenges confronting cities as they expand amid rapid urbanisation and calls for changes especially for regional and large-scale infrastructure projects involving jurisdictional cooperation. Notably, the Philippine New Urban Agenda identifies, as among the priority items: “Establish and support more effective sector leadership in a new urban governance framework with clear and well-defined multi-level and inter-government relationships” (Agenda 4.1); and “Encourage metropolitan governance for efficient spatial and functional interrelations between cities, settlements, and their surrounding areas” (Agenda 4.6).[1]However, the country’s decentralisation system remains unconducive for inter-jurisdictional cooperation. While both the 1987 Constitution and the 1991 Local Government Code provide for interlocal cooperation, without a political mandate for metropolitan governance, interlocal collaborations and joined-up approaches among connecting cities and municipalities become contingent on political alignments, as demonstrated by the cases of Metro Cebu and Metro Iloilo presented below. The paper contributes insights toward a responsive reframing of the country’s decentralisation regime to rethink political mandates for metropolitan governance, as a key policy strategy in advancing the country’s New Urban Agenda.

The Policy Problem

The Philippines’ current institutional design for metropolitan governance remains poorly equipped to manage transboundary, climate change-induced challenges in growing urban regions. Existing governance structures often lack the capacity for metropolitan-scale planning, coordination, and operation in areas such as risk management, adaptation, and disaster resilience. Case studies from Metro Cebu and Metro Iloilo reveal critical weaknesses in the systems of co-responsibility among neighbouring local governments, where collaboration is often ad hoc and politically contingent. The absence of formalised metropolitan institutions, combined with entrenched local political interests, hinders effective integrated risk governance. Without structural reforms, metropolitan regions will continue to face mounting vulnerabilities, undermining efforts toward climate resilience and sustainable urban development. This paper identifies these institutional shortcomings and offers policy recommendations to address the deep-seated political and administrative barriers to effective metropolitan governance.

SCALAR POLITICS: THE CASE FOR REGULATION IN NETWORKED GOVERNANCE

As cities continuously change and evolve under various pressures such as rapid urbanisation and the interlinking concerns and transboundary disasters, new imperatives emerge for corresponding (re)design of appropriate institutional and political arrangements that could effectively respond to not only managing integrated urban economies, but also managing integrated urban risks and their variability. Amid increasing connectivity of networked political geographies in facilitating urban resilience and sustainability, governments are compelled to work transversally across ministries, departments, and political jurisdictions at all levels to help governments break institutional and political silos. [MOU1] Intersections in governance mandates across levels and agencies are often urgent in integrated interventions like land use, flood and river management, water and air quality management, mass transportation, housing, climate change and pandemic response, among others. The 2022 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction reasserted this in its call for the transformation of risk governance mechanisms to ensure that management of risks is a shared responsibility across sectors, systems, scales and borders.

The metropolitan region is gaining salience as a crucial scale for positioning urban risk governance capacity. However, metropolitan regions are characterised by a ‘multiplicity of political jurisdictions’ (Ostrom et al. 1961) with many centres of decision-making (McGinnis 1999) that are formally independent of each other at different governance scales. Metropolitan governance exposes how power relations and hierarchies operate across translocal spaces and scales. It is therefore predominantly seen as a context that centres and operates on inter-jurisdictional collaboration and coordination, which requires negotiations and agreements for allocation and sharing of resources and responsibilities, toward collective action among neighbouring cities vis-à-vis central structures. Sellers and Hoffman-Martinot (2009, 262) would however argue that collective action within many metropolitan regions “[...] must overcome institutional fragmentation due to the lack of a central, encompassing regulatory authority.”

These highlight the need to rethink how political power is organised across different levels of government. Known as scalar politics, this process involves changes in how governance boundaries are drawn, driven by shifting power dynamics and geographic realities. It often leads to territorialisation—the creation of new laws, regulations, and authorities that reshape how people interact with their environment, especially in terms of who can access, control, and manage resources (Bassett and Gautier 2014, 2). As scales of disasters and urban development are altered, so shall the power structures involved in metropolitan governance be.

As Porst and Sakdaporlak (2017, 118) would argue: “Scale serves as one means to apprehend power in socio-spatial relations [...] translocal concepts draw on scale to address disparate magnitudes of power and unequal relationships between actors, neighborhoods, and nation-states[…].” Thus, if governments are to effectively manage transboundary urban issues, a rethinking of effective regulation of networked governance through political mandates for metropolitan structures becomes key. As Pollitt (2003, 4) earlier asserted within the paradigm of ‘joined-up government’, one of the key elements for regulation in networked governance is “[...] the ability to manage the issue horizontally across government by giving importance to a top-level steering and coordinating body that has political clout and action levers.”

INSTITUTIONAL GAPS FOR METROPOLITAN GOVERNANCE IN THE PHILIPPINES

Metropolitan regions in the Philippines are characterised by complex jurisdictional structures, which often create structural challenges of coordination in urban development, including transboundary urban risk governance. The local government structure outlined in the 1991 Philippine Local Government Code constitutes a three-tier system of local governance. This starts with the provincial governments on the first tier, then below are the component city and municipal governments under the province’ supervision, and at the bottom tier are the barangays. Highly urbanised non-component cities at the second tier, however, are independent from the province and relate directly to the national government (Section 29). Often, they serve as the core of the metropolis having the largest population and as major drivers of economic activity, and thus tend to take leadership in inter-jurisdiction metropolitan affairs and predominate in regional development.

There is essentially no metropolitan government. For shared interjurisdictional concerns, Section 33 of the Code mainly provides for interlocal cooperation, encouraging “cooperative undertakings among local government units … for purposes commonly beneficial to them.” In Metro Manila – the country’s largest metropolis – the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) which was created by Republic Act No. 7924 on March 1, 1995 manages and coordinates metro-wide services, including development planning, traffic management, and other essential services. It nonetheless has no political power, no governor, and operates under the direct supervision of the Office of the President. MMDA has no counterpart in the large metropolitan areas outside of the National Capital Region. Thus, to respond to their interjurisdictional concerns, other metropolitan regions rely on cooperative undertakings through memorandum of agreements (MOAs) facilitated by their respective Regional Development Councils (RDCs) - the highest planning and policy-making body in the country’s administrative regions. The RDCs serve as a forum where local efforts are related and integrated with national development priorities. These cooperative undertakings, however proved contingent on political alignments to work. The political constraints are exemplified by the cases of Metro Cebu and Metro Iloilo, which put into question the viability of existing metropolitan bodies absent political mandate. Both metropolitan regions are significant urban areas outside of Metro Manila, serving as major economic and commercial hubs in the Visayas region. Their core cities, Cebu City and Iloilo City have long competed for the title of “Queen City of the South” for their historical significance and economic competitiveness. Metro Cebu’s developmental decline however drew comparisons to Metro Iloilo’s recent developmental successes attributed to an effective development coalition (see Arcala Hall 2024).

The discussion below illustrates that the difference between the two in metropolitan governance have been largely based on sustained political alignment in Metro Iloilo which facilitated cohesion, where Metro Cebu struggled with since its economic boom. However, recent political tensions in Metro Iloilo since the retirement of former Senator Franklin Drilon – regarded as pillar of its development coalition - may just be indicating a growing jurisdictional fragmentation akin to Metro Cebu that exposes the vulnerability of a metropolitan coordination anchored mainly in political alliance.

Metro Cebu: Contestations over metropolitan leadership and jurisdictional battles

Metro Cebu is the country’s second-largest metropolis outside of Metro Manila. The metropolitan area is recently defined as comprising a total of thirteen LGUs, three of which are “highly urbanised” non-component cities (not under the province of Cebu), and ten (four cities and six municipalities) are component units of the province supervised by the provincial governor. These LGUs are unequal in size (area and population), income and revenue capacities, and geographic endowments and vulnerabilities. Cebu City as the capital of Cebu is also the core of the metro, exerting preeminence as the center of major economic activities and services. Hutchcroft and Gera (2024, 267) highlighted the inherent problems of coordination that arise from this complex structure:

(T)he creation of more effective metropolitan governance must contend with two major centres of power that – by virtue of existing jurisdictional structures – are frequently at odds. Firstly, the provincial governor has a natural interest in watching over the ten LGUs that are a part of both the province and the Cebu metropolitan area. The governor's concern for the three non-component cities comes not from formal supervisory duties but rather from a potential ambition to assert broader political influence. Secondly, the mayor of the pre-eminent city may reasonably want to assume a pre-eminent role in determining the policy directions of metropolitan governance. (The fizzling of “Ceboom”: How jurisdictional battles and warring factions undermined Cebu’s development coalition, 2024, p. 267)

The competition of Cebu City government and Cebu Provincial government over metropolitan leadership can be traced since the 1980s with the Metro Cebu Planning Advisory Council, to the Metro Cebu Development Council (MCDC), up to the latest initiative with the Metro Cebu Development and Coordinating Board (MCDCB). All these bodies were created through RDC resolutions. These initiatives however proved to have worked only in periods where the Cebu City mayor and the Cebu provincial governor are allies, such as in the golden years of ‘Ceboom’ where cousins Cebu City Mayor Tommy Osmeña closely cooperated with then Cebu Provincial Governor Lito Osmeña who also later channelled critical projects for Cebu as adviser on national “flagship” projects under the Ramos administration. Mayor Tommy Osmeña who largely predominated Cebu City leadership for about three decades, would however lose interest in metropolitan-based undertakings with the growing influence of a non-allied governor who would predominate metropolitan affairs. This would initially translate to standoffs and power struggles in mobilising support for priority projects, which led to unilateral withdrawals of Cebu City under Osmeña, first from the MCDC and then from the MCDCB. The Osmeña administration argued that the mayor’s accountability was only to his constituency, and that these metropolitan bodies have no proper jurisdiction and political mandate, and thus no legitimacy in coordinating different politically sovereign LGUs (see Hutchcroft and Gera’s 2024 analysis on the fizzling of “Ceboom”).

Throughout, Cebu City’s cooperation in metropolitan initiatives fluctuated based on either political alliance or conflict with the province or with other member LGUs. The lack of political mandate and regulatory jurisdiction over its members ultimately subjected the viability of metropolitan bodies to these shifts in political alignments. City and municipal governments may also elect not to adhere to the recommendations thus metropolitan and regional administrative bodies could not enforce accountability and cooperation (Mercado 1998). These would derail the implementation of urban master development plans that include projects for integrated land use, transport and flood control and drainage management designed to promote sustainability and resilience. Gera (2018) noted that political clashes among local government leaders constrained the implementation of projects such as the JICA-funded Metro Cebu Development Project (MCDP) to improve traffic networks, with certain LGU members complaining about the monopoly by highly urbanised cities of project allocations, which were predominating in decisions. In the end, local political officials would rather negotiate directly with national line agencies via Congressional patronage to have their development projects aligned to such agencies’ investment programming, often bypassing RDC and metropolitan bodies. The MCDCB - the last of such bodies - was ultimately dissolved in 2020. Since then, the RDC took over metropolitan coordination with efforts such as facilitating a technical working group on the Metro Cebu Integrated Flood Control and Drainage System Master Plan to go over the proposed flood control and drainage projects for funding and implementation by the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). It also facilitates city-to-city MOAs for their shared trans-local concerns such as the ‘Beyond Borders’ project - the transboundary river rehabilitation joint initiative between the cities of Cebu and Mandaue. However, without real political clout, the regional steering by the RDC could not address prevailing fragmentation amid cooperation anchored mainly in political alignments.

Metro Iloilo: Sustained political alignment but centrally-dependent

An emerging metropolitan center in the Philippines is Metro Iloilo, with Iloilo City at its core. Metro Iloilo has been noted for its development success in the past two decades with remarkable upsurge of big-ticket infrastructure projects and urban development based on strategic metropolitan planning. Arcala Hall (2024) attributes Metro Iloilo’s success to a development alliance involving multi-term city mayors and networked local business groups orchestrated by the political machine of former Senator Franklin Drilon. Akin to the ‘Ceboom’ years of Metro Cebu, there is a vertical integration into national, regional, and global networks, which provided Metro Iloilo a continuing inflow of investments. Similar to Lito Osmeña in Cebu, Drilon is largely acknowledged to have funnelled key infrastructure projects, especially for Iloilo City. Meanwhile, the prolonged tenure in office among city mayors (similar to the earlier predominance of Tommy Osmeña in Cebu City) due to uncompetitive local elections and tight political alignments, afforded a stable political leadership that ensured long-term planning around key infrastructure projects.

The difference is that metropolitan cooperation was sustained by the enduring alliance between the Iloilo City mayor and the provincial governors of Iloilo and Guimaras . The Mayor of Iloilo City serves as Chairperson along with the Provincial Governor of Guimaras as co-Chairperson of the Metro Iloilo-Guimaras Economic Development Council (MIGEDC). Unlike in Metro Cebu, the governor of Iloilo province does not compete for leadership in the metropolitan body. The MIGEDC established through Executive Order No. 559, s. 2006 is tasked with formulating, coordinating, and monitoring programs, projects, and activities to accelerate the economic growth and spatial development of the metropolitan area composed of Iloilo City at the core, along with six municipalities in the province of Iloilo around it, as well as the entire province of Guimaras. Its antecedents include the Metropolitan Iloilo Development Council (MIDC) established in 2001 through a MOA between Iloilo City and four nearby municipalities; and the Guimaras-Iloilo City Alliance (GICA), formed in 2005 through a MOA between Iloilo City and the province of Guimaras.

This cooperation had its earlier constraints. Mercado and Anlocotan (1998, 2) noted the incessant political bickering in Iloilo City during the first half of the 90’s which delayed long-term cooperative development efforts. The operationalisation of MIDC was stalled by the political stalemate between the mayor and the city council which refused to issue a resolution after alleging that the mayor acted on his own and that the city of Iloilo would be carrying most of the financial burden entailed by this metropolitan arrangement. Nonetheless, the stable political alignment between the key local chief executives led to joint resolutions for climate change adaptation and flood risk resilience measures such as the "institutionalisation of co-beneficial infrastructure, social, economic, and environment development plans and programs with the private sector that will enhance flood resilience in the City and the Province of Iloilo" (Climate Change Commission 2020).

And yet, these joint endeavours couldn’t deliver much. The increasing severity of flooding in Metro Iloilo exposes the continued lack of comprehensive flood risk assessment and integrated land use planning for the metropolis. Mayor Treñas points to the DPWH as accountable for the lack of interconnected drainage systems (Lozada 2024). He would nevertheless acknowledge that while the DPWH oversees the planning and execution of infrastructure development at the regional and provincial levels, the effectiveness of these measures relies heavily on their integration with local government drainage systems. This reveals the continuing fragmentation of drainage and flood control master plans among local governments. This also reflects the same observation of water governance in Metro Iloilo which continues to face coordination challenges with a large number of institutional actors with overlapping and sometimes unclear mandates and authorities (see Vogel et al.’s 2013 analysis on water security in Iloilo pp. 15-16). Iloilo still grapples with coming up with a comprehensive water action management plan amid reported land subsidence from water extraction (Daily Guardian 2024). Moreover, the discussion paper of UP CIDS-Urban Studies Program points to the fragmented institutional arrangements in the management of Iloilo-Batiano River System water quality. Moscoso et al. (2025) highlight the exclusion of other concerned LGUs and disparities in local ordinances and regulatory frameworks in the management of shared river resources, despite advances made by the Iloilo-Batiano River Development Council. These raise questions on the viability of MIGEDC to take on the responsibility for integrated metropolitan development and resilience planning and coordination.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

So far, attempts at metropolitan governance and coordination, absent effective political authority and mandates, have failed as they continue to be anchored in political alignments that are vulnerable to local power shifts. As the cases of Metro Cebu and Metro Iloilo have demonstrated, these have either upended collaborative efforts for integrated flood control and drainage master plans, or perpetuated dependence on nationally-determined interventions that could not fully respond to local needs and priorities.

The Philippines is certainly in a critical juncture to seriously take stock on the viability of the design of its local government structure to be able to climate proof its major urban centers. A responsive reframing of local and metropolitan regulatory authorities, in accordance with required scales and functional scopes of integrated risk and adaptation interventions, is imperative if the government is to seriously advance its new urban agenda. Key institutional reform strategies can be incrementally undertaken towards creating effective and enduring public sector institutions for metropolitan governance.

Revisit the role and authority of the RDCs in facilitating the vertical integration of cities and municipalities in the metropolitan region with the concerned national agencies.

As Hutchcroft and Gera (2022, 153) emphasised: “the regions sit at the most critical nexus between the national government and the local governments, they are the logical place to start in moving toward the goal of promoting an effective system of central steering in the Philippines.” While serving as representatives of the national government in the regions, RDCs shall initiate mechanisms of multi-level collaboration among LGUs, so their local needs and priorities are appropriately linked to and addressed by national programs and projects, and not the other way around (i.e. as local governments having to compete or negotiate to have their development projects aligned in national programs and RDCs merely serving as national mouthpiece). It shall serve as the core in metropolitan development planning and coordination that also integrates disaster and risk planning and reconciles disjointed, jurisdiction-based local development and risk management plans, and facilitate deliberation in allocating accountabilities.

Enact metropolitan authorities for metropolitan regions outside of the National Capital Region.

There are already attempts at legislating a Metro Cebu Development Authority (MCDA) akin to the MMDA to address transboundary problems. These bills however do not address the structural obstacle of competition between the provincial governor and Cebu City mayor in Metro Cebu by proposing that leadership “will be determined by the governor and the city and town mayors, with each member having one vote” (in Hutchcroft and Gera 2024, 269). A bureaucrat-led system that is determined by the central government may reduce political disputes among conflicting local chief executives. But as the experience of the MMDA would also demonstrate, its limited bureaucratic authority cannot fully apprehend local political power.

Ultimately, the country can pursue a recalibration of power structures within the country’s intergovernmental political systems, and a corresponding (re)construction of the scale and functional scope of the metropolitan regions.

The power dimensions of scale bring to the fore the agenda for designing an appropriate political configuration that can accordingly respond to the spatial and political fragmentation inherent in metropolitan regions. This means amending the Local Government Code to define and enact political powers for metropolitan governance structures that can respond to political-territorial dimensions of urban climate resilience and sustainability initiatives at scale. Regulatory enforcement by a politically legitimate metropolitan government would certainly have more clout and action levers to apprehend critical inter-jurisdictional collaborations. As it stands, the 34-year old Code represents what Lebel and Lebel (2018, 618) regard as “institutional traps” that is creating a barrier to improving collaborative urban risk governance in a nation reeling in climate change vulnerability.

These are certainly not often straightforward. Urban development after all is rarely contained by administrative and political boundaries. Even highly developed societies continue to grapple with attempts at metropolitan governance reform. Most decisions that affect metropolitan scale in Australian cities such as planning, transport and urban growth, are notably overseen by state governments, with little scope for formal local government collaboration (based on a 2021 AHURi Report). Nonetheless, I argue that institutions can structure synergy in decision-making and apprehend power. As the OECD (2021,3) contends: “identified challenges resulting from the mostly informal metropolitan governance arrangements could be overcome by further institutionalisation.”